What do I do for a living?

A brutally honest take on Product Management, and what comes next...

This post is inspired by all the genuine (and sometimes rhetoric) questions that people around me ask all the time.

“So, what do you do for work?”

“What do you actually do for work?”

“So you attend meetings, and…?”

“You got no hard skills, that’s why you chose PM hahaha”

Well, the last one may be true to some degree, but through this post I don’t want to defend what I do. I want to explain my role in the context of the changing times. Knowledge work as we know it, will change, and here’s me thinking out loud how these changes could affect our kind.

This is the first part where I try to explain, in very simple/honest terms and illustrations, what do I do for a living. In the second part, I’ll try to dissect why and how my role won’t look the same in the next few years (and so will yours).

So, what do I really do for a living?

My job title reads: Product Manager1 at Atlassian.

And I’m being honest with you: I get paid a fair bit for whatever I do and sometimes it’s hard for even me to understand why am I even getting anything in a world where engineers code, designers design and salespeople sell.

This is a source of imposter’s syndrome for a lot of people like me: this nagging feeling of we don’t deserve to be where we are.

But here’s what: we’re wired to understand labour but not leverage. That alone makes a world of difference.

But wait, what do I do again?

I earlier used to define my role as “the art and science of building the right products for the right people.” This even has some semblance of truth in it. But it doesn’t go on to explain what I’m exactly responsible for.

I loved this definition by the OG Lenny Rachitsky in his blog post: What is Product Management

Your job as a PM is to deliver business impact by marshaling the resources of your team to identify and solve the most impactful customer problems.

That’s essentially it. It’s all communication and leverage.

As much as I hate to say it as an engineer-by-degree, PM is very much a business-first role.2

Your job as a PM is to read the users better than they can tell it themselves, and build exactly the product that your company can expect sell them. You have to do everything in power to make sure that happens.

Marshaling resources could mean convincing your business unit that your idea will generate value for the business. It could also mean convincing your engineers that they’re working on the right problems and prioritizing their long to-do list of pending items. It could so as far as disagreeing with your leadership team to say that the strategy that they’ve sketched out sounds good on paper but it’s gonna be a disaster in practice, but you go ahead and do it anyway

So typically in a PM role, there are different seniorities. The more you grow in your role, the more forward-looking you have to be. The more senior you are, the more high-leverage problems you pick up. You grow in your role from owning features to owning product lines.

Example: A junior PM in Google might be responsible of making sure that the Archive feature in Gmail works as expected, a Senior VP might be responsible for the success of the entire Google Workspace suite.

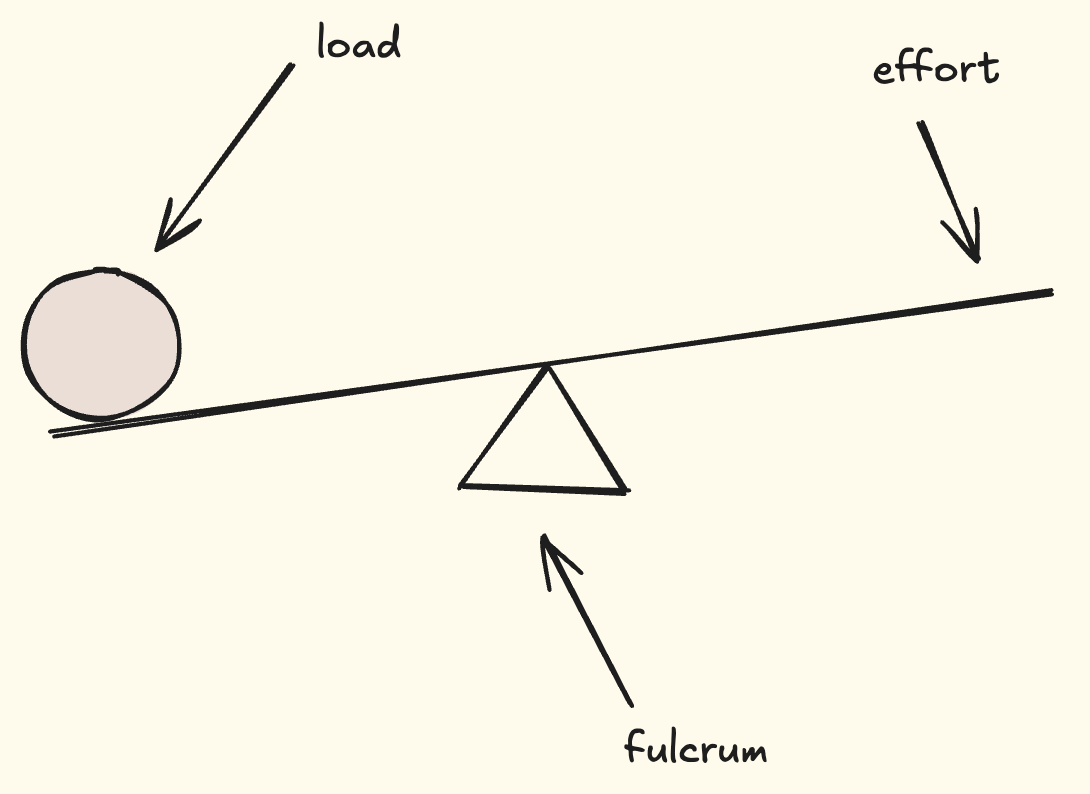

Hold on, what’s this leverage thing you keep talking about?

Glad you asked (or at least I imagined you’d ask).

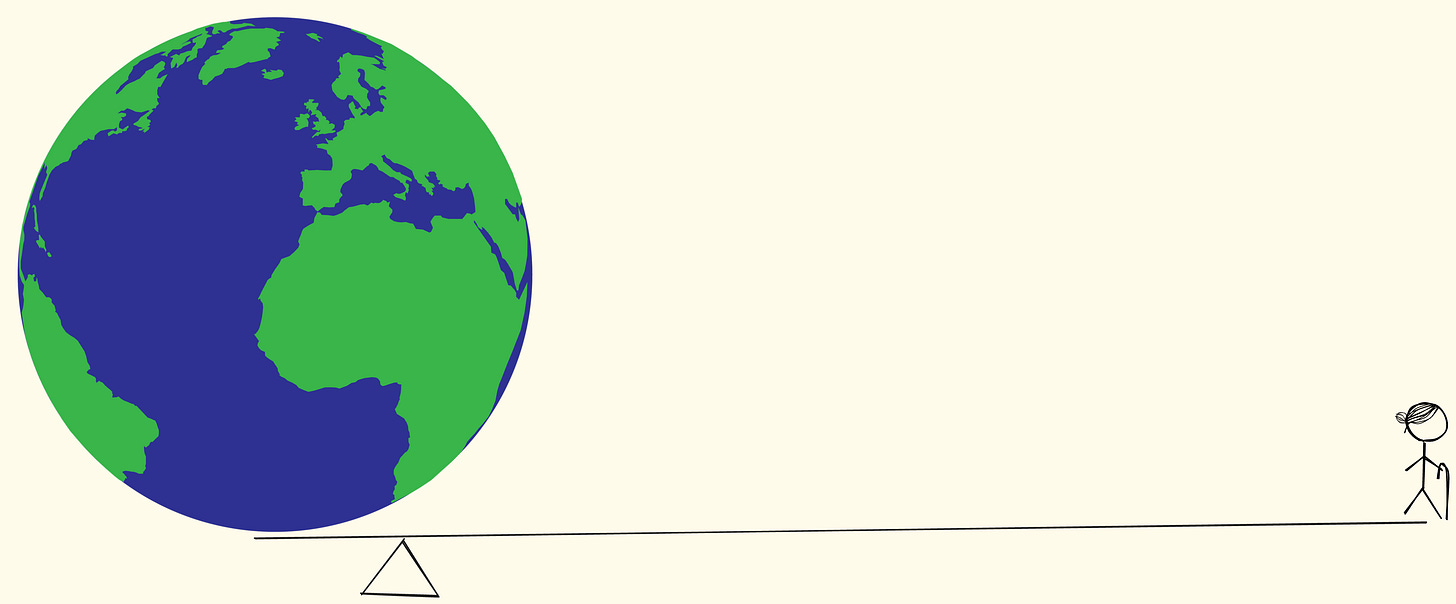

Leverage is derived from the word lever, which is, simply-put, a see-saw.

If the load were 69 kg, I’d be able to move it even if the fulcrum was in the middle. No, I’m serious about that number.

If the load were 120 kg I’d still be able to (theoretically) move the load if I was allowed to move the fulcrum.

Archimedes said: “Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it, and I shall move the world.”

Again, not sure where he’d order that kind of a lever from, but let’s believe him for a sec for he’s Archimedes at the end of the day.

I created a fun little lever-simulator-thing: lever.masaladew.com. Will keep adding more to it whenever I get the chance!

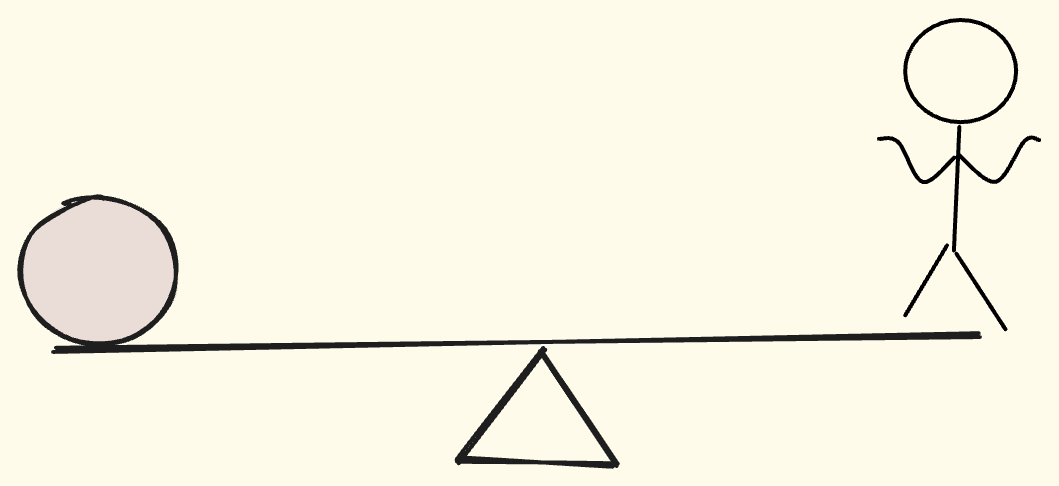

But in principle, what it means is that you can take up big problems and solve them if you can marshal a group of people towards solving it.

This act of marshaling is neither easy nor is as jolly as it might seem.

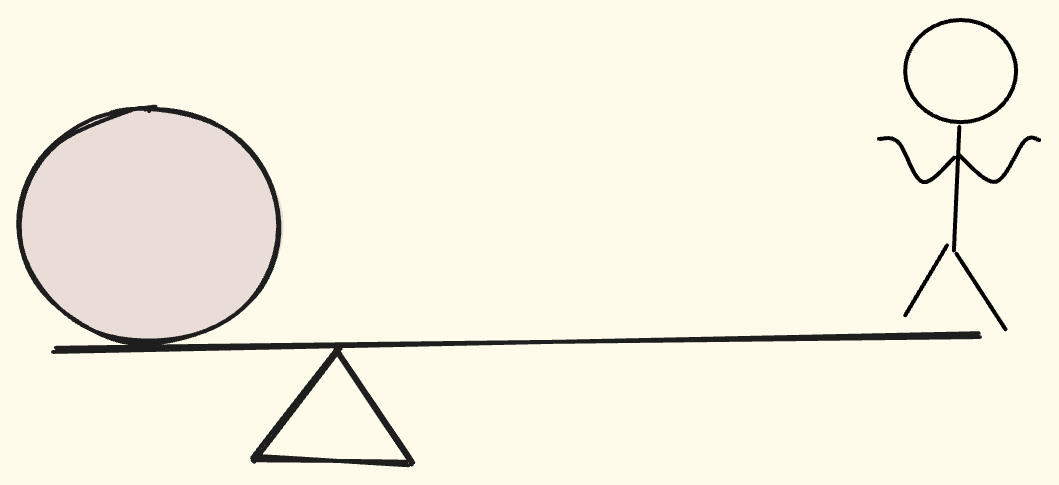

Imagine building a new product because your competitor has done it, and because you’re as big as them. Only to realize that it was such a disaster that despite your best attempts it didn’t amount to much and you had to shut it down (cough Google+3 cough).

Or that kernel update which went out and wrecked havoc on 8.5 million devices across the globe: freezing banks, delaying flights and effectively sterlizing most of the work PCs running Windows (cough Crowdstrike4 cough).

Or that AI-based customer support system that resulted in a lot of support staff being laid off, only to be boarded back again because oh it wasn’t working so well after all (cough Klarna5 cough).

To be clear: It’s NOT that these companies were plain careless and over-the-top as it might look from the outside — in fact, they had all the reasons to do what they did. But of the millions of things that could go wrong, a couple did despite the best efforts (except the third one, of course). And that’s all it takes.

Or simply that your engineering, business, design teams are understaffed/unmotivated for any of the million possible reasons — doesn’t matter, it all comes back at you. After all, your team’s performance is eventually your performance.

In essence, a bunch of things can go wrong between ideation, development, deployment and maintenance. You just gotta ensure that things work out as planned. Simple? Maybe. Easy? No.

As as a PM, you’re held responsible for it all.

That’s both a blessing and a curse of being in a role which mostly revolves around communication and decision-making.

In practice, I spend most of my time doing the following:

Prioritize asks coming in from various people into an easy-to-digest roadmap for our development teams, making adjustments as needed.

Write requirement docs (what has to be built and why) for product teams.

Keep checking-in with my engineering, business and design counterparts, either through text or video calls to make sure they’re unstuck.

Bring up any open questions to relevant forums and initiate a lot of external comms.

Pitch and prepare team wins, metrics, etc. to report back to leadership.

Keep an eye out on the what’s going on within the company and in the industry and keep bringing up new things to work on.

Create and respond to a TON of Jira tickets and Confluence pages.

Be prepared to be pulled into any leadership escalations where you have to justify why a certain project was delayed by x days/weeks or de-priortized.

If any of those things seem fun to you, yes that’s a part of the job. If any of these sound scary/icky to you, they’re still part of the job and the curse of this thing called leverage — the independence of being able to take decisions on your team’s behalf.

Someone jokingly said in my office: “As a PM you’re the last one to get appreciated when anything goes right, and the first one to be hounded when anything goes wrong.”

Seems like he wasn’t kidding anyway.

Let’s describe this with a oversimplified-but-real-life example

This one’s a classic.

In my company, I work on the billing engine and experience of our customers, which sees billions of dollars flowing through it every year.

In my role, I was asked to do something to improve the number of customer support tickets that we were getting in any given month so that our support team could breathe and respond to the more important ones.

What I started doing was figure out what kinds of tickets were coming at us and why were they taking so long to respond.

It turns out that the issue was relatively simple; the support team was taking up complex asks from our larger customers, leaving behind tickets which were “low” in priority in their classification. This led to a surge in the number of tickets and a breach of the response time that we assure customer (we’ll get back to you in 1-3 business days, only that our business days were from the moon).

What we started doing was explore an automation which was being used by a different support team and rebuild it according to obey the rules of our billing engine. We allowed the automation to take a first stab at the problem, place an order and respond back to the customer on behalf of the support team.

We faced some issues here and there, but eventually the automation started taking up around 40% of all support tickets. I got promoted (wuhuu).

Okay, enough about me.

I know I haven’t done a very comprehensive job of explaining what did I do to get here and why, but there are a million resources available that will do a far better job at explain those bits to you. Some of my favourites:

Exponent (YouTube channel — prep-friendly material)

PM School (YouTube channel — prep-friendly material, Indian context)

Lenny Rachitsky (Podcast, Newsletter (paid) — great speaker lineup and excellent industry insights)

Aakash Gupta (Podcast, Newsletter (paid) — practical resources and career advancement stuff)

Just like you all, I’ve been thinking a lot about how this new wave of artificial intelligence and automation will change the way I look at the world. More importantly, how good or bad can it be for me in the short-to-medium term. Should I upskill in my product craft or should I explore setting up a small farm of organic vegetables?

More on that in a post to follow.

After a re-org earlier this year, I’m working under a “Technical Program Manager” title. Same same but different.

I’d go as far as saying that there are only types of roles in the world: business roles and craft roles, and if you’re working in any company, these business roles will keep on increasing. But more on that later.

For the young ones: Google+ was Google’s attempt at social media, trying to rival Facebook back in early 2010s. My hypothesis is that Meta’s Threads is now running on similarly thin lines, but there are some ways in which they could save themselves. More on that later.

This one’s much more recent and you’d remember it: those BSoDs that appeared on every Windows Enterprise computer around the world? Yes, pretty insane.